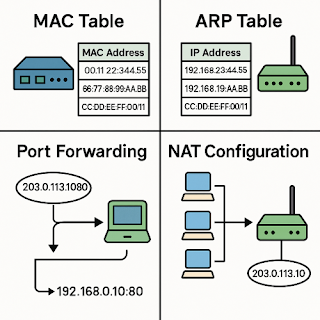

Utilizing MAC Table and ARP Table with Port Forwarding and NAT Configuration Strategies

To manage modern network environments efficiently, it's essential to understand and apply the concepts of MAC tables, ARP tables, port forwarding, and NAT (Network Address Translation). These four components play a crucial role in everything from home internet to enterprise networks and server administration.

This post explains the roles of MAC and ARP tables and explores port forwarding and NAT strategies to help you build a more effective network environment.

MAC Table: Internal Address Book of Switches

The MAC (Media Access Control) table is a database used within network switches that records MAC addresses and the corresponding ports to which they're connected. It allows the switch to forward packets efficiently.

- The switch learns the source MAC address from incoming packets.

- If the destination MAC is found in the MAC table, it forwards only to the associated port.

- If not found, it broadcasts to all ports.

The MAC table is updated over time to adapt to changes in the network and maintain stable connections.

ARP Table: Translating IP to MAC

The ARP (Address Resolution Protocol) table maps IP addresses to MAC addresses, primarily used by routers and hosts. It translates Layer 3 IP addresses to Layer 2 MAC addresses for data transmission.

- When a host doesn’t know the MAC address of a target IP, it sends an ARP request.

- Once the reply is received, the result is cached in the ARP table.

- This reduces unnecessary ARP traffic and improves speed.

Because it updates in real-time, the ARP table directly affects network performance and security.

Port Forwarding: Bridging External to Internal Networks

Port forwarding allows external devices to access specific devices or services within a private network. It is typically set up on routers or firewalls and is essential for enabling remote access to internal web servers, NAS devices, and CCTV systems.

Example:

- Public IP: 203.0.113.15

- External port: 8080

- Internal IP: 192.168.0.100

- Internal port: 80 (web server)

A request to 203.0.113.15:8080 is redirected to 192.168.0.100:80. This provides access to the internal web server from the outside.

Tips:

- Only open necessary ports to reduce security risks.

- Use DDNS for stable access from changing public IPs.

- Disable UPnP and configure port forwarding manually for better security.

NAT Configuration: Internet Access for Private Networks

NAT (Network Address Translation) allows devices on a private network to access the internet using a shared public IP address. It's an essential component for modern internet access.

1) SNAT (Source NAT)

Changes the source IP of outbound traffic to the router’s public IP.

2) DNAT (Destination NAT)

Changes the destination IP of inbound traffic to a private IP. Port forwarding is a type of DNAT.

Key factors in NAT planning:

- Ensure connection tracking (conntrack) limits are adequate.

- Use clear port mappings for each service.

- Design a logical private IP structure (e.g., 192.168.0.0/24).

Since NAT manages port numbers in addition to IPs, exceeding the session limit may cause disconnections. Consider a high-performance router for intensive use.

Suggested Setup for Home and Small Office

For homes and small businesses, a robust network setup may look like this:

- Use DHCP for general devices (e.g., 192.168.0.100–199).

- Assign static IPs to servers and NAS (e.g., 192.168.0.10).

- Set up port forwarding for specific services (e.g., ports 443, 8080, 5000).

- Regularly inspect MAC and ARP tables for network health.

This structure balances flexibility, security, and ease of maintenance while ensuring future scalability.

Conclusion

MAC tables and ARP tables ensure smooth internal communication, while port forwarding and NAT enable controlled external access. When used properly, these technologies form a solid foundation for building fast, secure, and scalable network environments.

A deep understanding of these components is vital for anyone managing a network—from small business admins to home network enthusiasts.